- HOME

- EXHIBITION

- Foreword

- Capture

- Portrait

- The State of Israel vs. Adolf Eichmann

- Eichmann on trial

- Verdict

- APPENDIX

- AROUND

THE EXHIBITION - VISITING INFORMATIONS

- FR - EN

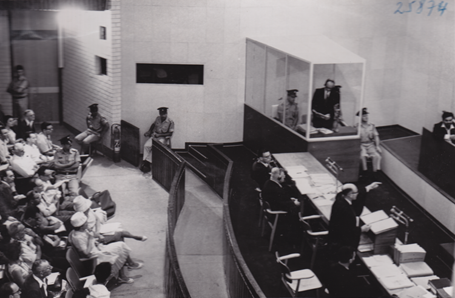

Eichmann on trial

The right to judge

«Jews had to fight for the right to judge Eichmann just as they had to fight so often in the past for a right granted to others without any discussion,» Attorney General Hausner wrote in 1966. He was referring to two issues: the trial´s legitimacy and its legal foundations, both of which were contested and interconnected. At Nuremberg the victors´ right to judge the vanquished was challenged. In Jerusalem it was the victims' right to judge the killers that was called into question.

Eichmann was judged under the 1950 Nazis and Nazi Collaborators Punishment Act, which established the death penalty for people found guilty of «crimes against the Jewish people» and «crimes against humanity», to which the statute of limitations do not apply, and «war crimes». The law was controversial from the start because of its departure from usual penal procedures. It is retroactive, covers crimes committed outside Israel and authorizes the prosecution of crimes that have already been tried. Applied to crimes committed against European Jewry perpetrated before the State of Israel's creation, it gives that country full, entire legitimacy to judge defendants on their behalf and on behalf of all Jews living or dead. The political, philosophical and legal debate that broke out at the time was a turning point in the history of the remembrance of the Shoah – and shows the difficulty of taking into account the historical singularity of a crime that targeted only Jews while at the same time asserting its universal character.

At the time, the players did not yet perceive the exemplary character of the trial, which was a big step towards punishing mass crimes. They saw it as part of a continuity. It was the heir to Nuremberg, whose traces were everywhere, from the documents used (including some from the Contemporary Jewish Documentation Centre in Paris) to the charges leveled (war crimes and crimes against humanity), the participation of certain players (judge Michael Musmanno and psychologist Gustave M. Gilbert, both of whom were called to the witness stand), the educational role accorded the witnesses and the films that were shown. The Israeli government also argued that the procedure must be compared to the postwar trials in all the formerly occupied countries judging Nazis and collaborators. The purge trials often provided an opportunity to reassert a national identity shaken by the war, Nazism and collaboration, as in France, where they took place largely to restore national dignity. Israel went the same way, seeking to show that the Jews are a people among others who were the Third Reich's victims. Punishing one of the European Jews´ murderers was a way to shore up the foundations of its existence.

Eichmann was indicted on 1 February 1961 and appeared before the Jerusalem District Court, an ordinary court rather than an exceptional tribunal, as the International Military Tribunal of Nuremberg or the courts that conducted most of the national purge trials were.

Responding to defense lawyer Servatius's objections, the presiding judge reads out the decision of the court, which declares itself competent to try Eichmann.

Coll. Israel State Archives/The Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archives of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the World Zionist Organization.

« The endless procession of witnesses… »

« who had come to relate their horrific ordeal » is how Israeli poet, journalist and writer Haim Gouri described one of the Eichmann trial´s most memorable facets: the testimony of over 100 witnesses, most of them survivors, all but two of them Jewish, nearly all of them speaking for the first time. Witnesses also testified for the defense; most of them were former Nazi officials whose depositions were taken in Germany. The witnesses spoke for hours and days on end, fearful of being able to find their words, of being disbelieved, of letting their children know about the suffering they had endured. The Eichmann trial gave witnesses a central and unusual role. Survivors revived memories of a past that had already faded so much for their contemporaries that the prosecution called a historian, Salo Baron, to the stand to recall what European Jewry had been like before 1939. They confronted generations unprepared to understand or even listen to them and were forced to relive their suffering, often with an intensity that time had not lessened; meanwhile, they had built new lives, experienced other joys and sorrows. The procession of survivors shook Israeli society and probably modified the country's image. It threw the founding image of heroic, fighting Jewry into sharp contrast with the massive, unfathomable reality of the extermination of nearly six million innocent civilians who had no desire to become martyrs of any past, present or future cause. In accordance with the wishes of Hausner and Ben-Gurion, many former resistance fighters, Warsaw Ghetto survivors and members of Jewish fighting organizations were called to testify. But that was not enough to bridge the gap between the images, and the worlds, of victims and heroes. In 1961 it was already hard to make use of the Shoah survivors´ words.

Prosecutor Bach questions Pinhas Freufiger, a leader of Budapest's orthodox community in 1944, who talks avour when he learned what happened to Hungarian Jews arriving at Auschwitz.

Coll. Israel State Archives/The Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archives of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the World Zionist Organization.

Abba Kovner was born in Ukraine in 1918, grew up in Vilnius, Lithuania, studied at the Hebrew Academy and the art school there and became an active member of the Socialist Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatza’ir. In June 1941 the Germans overran Lithuania and built the Vilnius ghetto but Kovner managed to escape and found refuge in a Dominican monastery near Vilnius. Later he returned to the ghetto and witnessed the massacre of thousands of Jews. That is when he decided to form a group of Jewish fighters that tried to kill German soldiers. Kovner became a well-known writer and a symbol of «Jewish vengeance». He testified on 4 May 1961

« Open the court up to the outside world »

On 8 November 1960 the Israeli government signed a contract with the Capital Cities Broadcasting Corporation to film the entire trial, scheduled to start a few months later. The idea was to widely broadcast an event the whole world sensed would be important, especially because of television, which did not yet exist in Israel but was growing by leaps and bounds in the United States and Europe. The decision to film it was based on the same rationale as at Nuremberg, history´s first great filmed trial, which produced archives for posterity. In the age of mass communication, it achieved two goals that any ordinary trial in democratic systems seeks to attain: the debates' oral and public nature, principles born in the Age of Enlightenment. The defendant´s, witnesses´ and other players´ right to speak freely forms the basis of the court´s legitimacy and the public nature of the examinations and cross-examinations ensure that justice is done.

Innovation was not without risks: Robert Servatius, Eichmann´s lawyer, objected that cameras might influence the witnesses and that the images could make a false impression, especially of the defense´s arguments. Others feared that the judges would lose control of the trial. But those partly-justified drawbacks did not outweigh the possibility offered by modern technology to leave a lasting record of the event and, above all, to «open the court up to a global public», in the words of Leo Hurwitz, the director chosen to film the debates, who produced an outstanding document whose excerpts you can see in this room.